- Home

- Zoe Valdes

The Weeping Woman Page 2

The Weeping Woman Read online

Page 2

It’s quite true what Doris Lessing wrote somewhere, about how men came into the world after women, how they’re inferior to us, and how some of us women act like such idiots we even envy men their good fortune and try to imitate them.

The elevator stopped at the floor where I was going. Even as I stepped out, I also thought about trifles such as forgetting to take out the garbage, forgetting to hem my daughter’s dress. Yes, that tends to happen to me, I mix up my more-or-less good ideas with everyday trivialities. “Nothing to feel guilty about,” I thought defensively.

Worse still are the women who make such a big deal of their gender that they start off using their vaginas as their ID cards and end up treating them as their bank accounts.

A man of about forty opened the green door for me; he had a very youthful appearance, but his face told another story, that he was forty or more years old and had been through a lot, yet he was still tall, dark, and handsome, with a nice body from working out. He didn’t introduce himself, didn’t give his name. Nor did he offer his hand affably, but instead comported himself as if stripped of emotion, and though it all happened very quickly he had time to make a show of curt officiousness. “A servant,” I immediately guessed.

All he politely asked of me was to sit in the living room, where he said I should wait for Monsieur Minoret (as he called Bernard). He was, without question, a fine-looking butler, attractive, discreet, and polite.

I nodded and slipped into the living room, one of my high heels catching on the worn carpet that filled the entire room from wall to wall, as antiquated as the elevator or older. The sofa was also green, the same hue as the door. The walls, illuminated by carnation-shaped lamps, shimmered in gold tones tinged with Venetian orange.

I studied the furnishings: refined, elegant, clean, each item a sign of its owner’s loyalty to a memory, an era, a person; a Picasso drawing, a portrait of Bernard. Another pointillist drawing, a profile of a young man whose gaze went off the paper and beyond the frame, toward a gloomy room aglow in Pompeiian green. Bernard now suddenly emerged from that very room and strode confidently to my side. Haughty, refined; in a few long strides there he was at my side, or at the side of his portrait hanging next to me, and he pointed to the framed, yellowing Bristol board.

“This is my favorite drawing, a portrait Dora Maar did of me,” he remarked with pride. “She gave it to me in exchange for lace and linens—shawls, sheets, pillowcases, curtains, a whole pile of bedding; she loved that sort of sophistication, white linens. But enough of that, let’s cut to the chase. I didn’t actually know Dora all that well, perhaps not very deeply, but I did have a certain friendship with her, brief but close, thanks to Lord. My real friend was Leonor Fini, among the highly intelligent, beautiful, and quite extraordinary women of that period. But the little I knew about Dora made an impression on me. Without a doubt, she was one of the most brilliant women I have ever met.”

I reminded Bernard that I was only interested in those five days in Venice (“Eight days, counting the return trip,” he reiterated), during which they must have talked about all sorts of personal, and very intimate, things. Was Dora really in love with James Lord? Was he with her? How did Bernard feel around the two of them?

“I felt quite at ease with her. Dora was charming with me. Nothing odd passed between us, except perhaps an intense spirit of rapport. The truth is, it was a trip on which nothing in particular happened. We just wanted to walk around, James and I, relive the city, visit the museums, the churches. Dora was going there for the first time. She had this dream of visiting Venice, and we made it come true. James wanted to give her the adventure she’d been itching for all her life. Well, ‘itching’ is a manner of speaking. At that time we used to travel by car, by train, and nothing ever tired us out, because we were full of aspirations, blooming with good health and life’s vigor. Doris arrived in Venice after James and me. We put up at the Hotel Europa and waited for her there. James and I had already ended a relationship that went beyond friendship; that is to say, our sex life had become less important to us, it barely existed. James was getting to know me in a different way, he was crazy about my compulsions, he catered to my smallest whims and desires. I was becoming reacquainted with Dora, and I loved seeing her act like a little girl, rushing to get to the canals, but instead of a walk along a canal, as many as there were, we’d wash up in a museum and pay homage to a sculpture or prostrate ourselves before a fantastic painting, the way people once venerated the Virgin in a shrine. We had an intensely good time on that trip, and culturally we grew even more. What I mean is, James and I grew more cultured, since Dora herself was already a woman with a great deal of culture. We were cultured, too, but being younger, less so.”

I asked Bernard, while sipping at the tap water I’d been served in fine Baccarat crystal, if Dora was a talkative sort, if she wore her feelings on her sleeve.

“No, not so much. She needed to be loved, that’s for sure. She was a middle-aged woman, mature, yet she behaved like a fifteen-year-old girl, like these shy young women who are also rebellious and brash and always demand to be the center of attention. I gave her a lot of attention and enjoyed talking with her about the little everyday things; we didn’t necessarily have any heavy, substantial conversations, nothing like that. Just simple topics. Or else she’d tell us the story of her life with Picasso, over and over again.”

“And James Lord?”

“James was a gentleman, a chevalier servant, a platonic lover. James is an extremely busy man, you should meet him; I’ll do what I can to introduce you two.… Should we head for the restaurant? I’m a bit worried, you see, it may be packed, it’s nearly lunchtime already. In Paris, kitchens close early.”

He stuck his arms through the sleeves of a beige raincoat.

“Aren’t you a little underdressed?” he asked, narrowing his eyes, which gave him a feline look.

I shook my head no, kept quiet, and took a last, panoramic look around.

Suddenly, Bernard spun round and ran to the room that I fancied Pompeiian, where he rummaged around in a drawer. I couldn’t see him from where I stood, but I heard his hands riffling through papers.

“I found what I wanted to give you! I almost forgot. The pages from my diary on that trip; I’ll make you a copy.”

I heard the screak of the copier continuously spitting out pages.

“They don’t say much, nothing terribly important, just a few notes I jotted down, and I don’t even remember when I wrote them, or why.”

I stuck the copies in my purse after giving them a once-over.

“I’ll read them when I get home, if you don’t mind.”

He said he didn’t, not at all, and also shook his head a vigorous no to tell me he didn’t mind one bit, then he wrapped a scarf around his neck, and we hurried off to the restaurant.

The Art Nouveau restaurant awning was also green, and the thick velvet curtain over the doorway was emerald, green as can be.

“Everything’s green as can be today,” I muttered.

“I like green, I have a lot of green in my life; it’s my favorite color,” Bernard said with infectious enthusiasm.

I began to ransack my brain for my own favorite color in case Bernard asked me, but he didn’t. Red, blue, yellow, ochre? Gold? I’d painted in gold a lot during a period in my life when I spent hours before canvases that ended up glowing in gold and copper. My paintings weren’t exactly sublime, quite the opposite, but I won’t die regretting that I never tried, that’s for sure.

No, he never even wondered what my favorite color was. He started reading the menu, though he already knew it by heart.

They sat us at a narrow little table by the door, and we ordered confit de canard, champagne, water, an apple tart with fresh cream, and coffee to finish off.

“This might come as a letdown, but I don’t have many stories about her to tell, only personal impressions, notes scattered in my memory like brush strokes, and also, of course, I’m proud to own s

everal of her works,” he whispered.

“Photographs or paintings?” I was much more interested in her photography, because, to tell the truth, I didn’t know all that much about her work as a painter.

“Paintings. Though she wasn’t a great painter. And of course, I have the drawings she did of me, and one very subtle landscape, in oils.”

“She was the greatest photographer of her time. She got into painting to humor Picasso. Everyone knows that she was the first to do a graphic study of a painter’s work in progress, and the painter was Picasso, and the painting was none other than his masterpiece, Guernica,” I recited.

“She wasn’t a bad painter, either,” Bernard quickly corrected himself. “That was her cross, she dug her own grave when she photographed Guernica. Picasso never forgave her.”

“I know. Someone even wrote that she was the one who suggested he should replace the sun in Guernica with a light bulb, and to top it off, she slammed him with, ‘You don’t know how to paint suns’ or ‘Your suns never come out right.’ On the other hand, when it comes to politics, let’s be honest.… Picasso had done nothing, or nearly nothing, either for or against his fellow Spaniards during their Civil War. Dora couldn’t stand that. She demanded, pleaded that he show them support, told him history would judge him if he didn’t. Is it true that Picasso had dealings with the Nazis, that he received them in his studio and sold them paintings? You know, some books have it that Hitler considered Picasso an enemy, but the Nazis dropped by to keep tabs on him, and, who knows. Paul Éluard said—”

Bernard burst out laughing. It was a small dining area, and people turned to look at us. I lowered my gaze and stared at my hands folded on the table. Sometimes I observe my hands as if they’re not mine, detached from me.

“What sort of books are you reading? Please, don’t get in so far over your head. Nobody goes around accusing Picasso, nobody speaks badly about him, back off, don’t touch. Picasso would never have done anything like that. Picasso, my dear, is a god. The Nazis banned his works, removed them from galleries, but he did feel forced to receive the Germans every time they dropped by. He wasn’t the only one, as you can imagine. Éluard could say whatever nonsense he wanted, yes, he could, and indeed he did.”

I bit my lower lip, embarrassed by my slipup; I sensed the snake was about to bite.

At a small table in front of us, a woman sat smoking, alone. She had finished her lunch and was flicking the ashes onto the leftovers on the plate. She had fleshy lips, a straight nose, a slightly protruding forehead. Her eyes were yellow, oddly puffy, the strangest greenish-yellow color.

“Behind you, Monsieur Minoret, there’s a woman with yellow eyes,” I whispered.

“Ah, yellow eyes! Like Jacques Dutronc, the singer and actor, the one who played Vincent Van Gogh on the screen. His eyes are the color of golden honey,” Bernard said without turning around. “Should we be on first names? Oh, I think we already went through this.” Again he turned his inquiring eyes on me.

I said, without looking away from the woman with the rounded head that reminded me of Dora Maar’s, that I preferred keeping things more formal. I could never talk to him as if we were old friends, it felt too uncomfortable.

He agreed with a shrug, acting cross.

“Tell me the truth. Why are you so interested in Dora Maar?” he asked while he rummaged through his sport coat pockets for something.

“Because she was a great artist, because she was an enigmatic woman, because she fell head-over-heels in love with Picasso and suffered in silence after their breakup. Apparently, she stopped having sex at thirty-eight. With all the friends she once had, she ended up completely alone. But after everything I’ve read about the people in her circle, I also became very interested in you. In your connection with Picasso, of course, and in you as a society person and a writer, and in Lord as the platonic lover. Isn’t it true that you all wanted to get at Picasso through her? I met Dora briefly, in passing.” I didn’t want to say any more.

He blinked at that last statement, but he saw how I was trembling and didn’t pursue it, latching onto what most interested him. “Dora gave up her sex life at thirty-six. But it was her choice. As for the rest of us trying to be friends with Picasso—what else would you expect? I mean, Picasso. Though I was already friends with him through other people.”

“She was already Dora Maar; when she and Picasso met, she was already a great artist, well-established and acclaimed by the Surrealists.”

“Of course, of course, but hardly anyone noticed that detail.”

“Detail? Sharing her life with Picasso was a detail? He wouldn’t have painted Guernica without her.”

“There are a lot of things Picasso wouldn’t have done without her. But he was Picasso.”

The woman in front of me looked at her watch, pulled a cell phone from her purse, dialed a number. She tried again and this time, it seemed from the way her face relaxed, the person on the other end had finally bothered to pick up. She talked with her free hand cupped over her mouth, while lowering her head to avoid the glances of the other diners. Soon enough, she put the phone away, lit another cigarette, lowered her eyes slightly, half-closing them. Now her eyes had a damp sheen and were speckled with tones of gray. She was weeping.

“Almost everything written about Picasso has it that Dora wept rivers, that she grimaced, screamed, and contorted her face until she looked horrible.”

“I never saw her weep, except in Picasso’s portraits.” Bernard sat entranced with the delicate play of light and shadow on the sidewalk, on the other side of the window that separated us from the street. “No, Dora wasn’t a crybaby, far from it. Not every book talks about her in such vain speculations, or falsehoods in my opinion, which not only attempt to drag her down, but also insult those of us who witnessed those years,” he declared.

I was tempted to tell him a bit more about myself, about my life in Cuba and my more recent life here in exile. I was about to assure him that I didn’t cry anymore, that my tears had dried. But sometimes I felt an anger burning deep down inside me, though by a great effort of spiritual concentration I could calm down. My blind rage would disappear as quickly as it had come. And, above all, I wanted to tell him, I felt very alone, profoundly vulnerable, with no one to help me. I didn’t say any of this, I kept quiet, as I tend to do more and more these days, keeping quiet and burying it all inside me. Then I write, which relieves me, and it seems I can forget everything that made me so furious. I’ve turned all my tears into written words. Everything I might have wept, I’ve poured out onto paper. I’ve set down everything I could have wept in writing. I opened my mouth, closed it, thinking better of telling him.

“You were about to say something?” He spoke to me in the informal tone that I felt unable to use with him.

“No, Monsieur Minoret, nothing important. It’s just that, well, you see, from where I’m sitting, there’s that woman in front of me, alone. She’s started crying, and now her eyes have turned gray.”

“Eyes that change colors like the weather. Dora had the most beautiful eyes, nothing escaped them. She saw what no one else could see. Don’t worry about that weeping woman. She isn’t a portrait by Picasso. And only portraits by Picasso deserve the attention of people like ourselves.”

“She could have been one of his models, she’s so beautiful,” I stuttered. “I’m not interested in Dora Maar because she was Picasso’s lover. I care about her apart from Picasso, because I was drawn to her life, and her art, and most of all to her work as a photographer. I’ve been a fan of hers since I saw her photograph, Père Ubu, with its deep meaning and immense Surrealist power. An enigmatic little animal with a hairless snout and outlandish claws. Though I also greatly admire the photos she took before she ended her affair with Georges Bataille: the exotic photos of Assia; Leonor Fini—another great Surrealist, from Argentina, just like Dora (that’s why they had so much in common); the portraits she printed of Picasso himself. I fell in love with her work a

nd the story of her later life. And then I was immediately intrigued by those five or eight days in Venice—eight, counting the return journey, of course. Such a strange trip, nobody knows the details except you two. At the time, as you know better than anyone, she was utterly devoted to James Lord, from romantic rather than maternal impulses, I’d guess, while he was more devoted to Picasso than to Dora, and perhaps more than to you as well. Who were you devoted to, emotionally?”

“Both of them, I was devoted to both. Or rather, I was devoted to belonging to the twentieth century. To becoming an icon. By then, on that trip, Dora had mellowed, she was easier to be around.”

“After that trip, Dora decided to break off all ties, she shut herself in her house on Rue de Savoie and rarely left except to go to Mass. She met with James Lord a few more times, shunned uninvited company,” I rasped. “You know, women who shut themselves off almost move me to tears.”

“This isn’t news to you if you’ve read a great deal about her, but I’ll remind you, Dora always said: ‘After Picasso, God.’” He ordered another coffee, black and strong.

“I know, I know, it makes sense. Surrealism set her free, and on the other hand, her love for Picasso turned her into a fugitive and at the same time imprisoned her in her own life story, a victim of her blind passion, silenced by her own frenzy.”

We got up to leave.

There, a short distance away, the woman was quietly dabbing her tears with a lace handkerchief embroidered with the initials E M. She didn’t even notice us leaving, saying goodbye to the owner of the restaurant, or, immediately afterwards, nodding in her direction. She never stopped staring straight ahead, on purpose, to avoid making eye contact with us, focusing on nothing, or perhaps on forgiveness, on the sadness of forgetting.

Out on the street, Bernard stopped me, gently grasping my elbow.

“Dora wasn’t such a creature of passion, don’t think that. Dora was an artist of great intelligence. Love overwhelmed her, made a fool of her.… She didn’t weep on the outside, she wept on the inside, let all her tears flow inward, flooding her soul.”

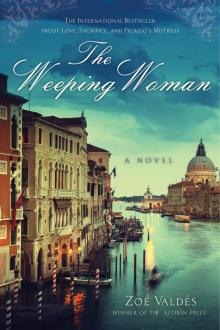

The Weeping Woman

The Weeping Woman